MiGs, Stars & Magic Books: A Brief History of Trespassing in Moscow

An illustrated guide to urban exploration in the Russian capital.

28 March 2016

Brooding ominously on the riverbank of southwest London sits a relic of a former age. Battersea Power Station, with its sleek, dark brickwork and noble chimneys, has made a defining mark on the city’s skyline for almost a century. Now however, after decades trapped in a limbo of failed redevelopment plans and gradual, creeping decay, the power station is finally being brought back to life as the heart of a new urban regeneration scheme.

With the help of a few friends, I managed to take an unofficial tour of the place as it stands today – a colossal ruin, a hulking remainder of Britain’s past, poised now on the eve of its glittering rebirth.

I was in love with Battersea Power Station since long before I knew what I was looking at.

I’d listened to the Pink Floyd album Animals [below right] at least a hundred times before I ever glimpsed the building in the flesh. But even then its shape was familiar – from the PC game Red Alert, with its power station units unmistakably modelled on the Battersea design.

I’d listened to the Pink Floyd album Animals [below right] at least a hundred times before I ever glimpsed the building in the flesh. But even then its shape was familiar – from the PC game Red Alert, with its power station units unmistakably modelled on the Battersea design.

I guess back then, I’d just assumed all power stations looked that way… but they don’t, far from it, and that’s what makes this structure so very special.

The exterior of Battersea Power Station was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect responsible for Britain’s iconic red phone boxes. The station belonged to a time when civic architecture took pride of place in urban centres; when the finest architects in the land were commissioned to build schools, bridges, pumping stations, hospitals and city infrastructure. Battersea belonged to an era in which even the London sewers were embellished with elaborate brickwork flourishes; an industrial society that raised power stations like the new cathedrals.

To borrow the cliché, they don’t make them like they used to. In post-war Britain, civic buildings were reduced to function without form. The new power stations built in the 1960s and 1970s were little more than grey boxes: just look at Heysham, Wylfa, Hartlepool and Dungeness; or Sir Basil Spence’s concrete cubes at Trawsfynydd Nuclear Power Station.

To borrow the cliché, they don’t make them like they used to. In post-war Britain, civic buildings were reduced to function without form. The new power stations built in the 1960s and 1970s were little more than grey boxes: just look at Heysham, Wylfa, Hartlepool and Dungeness; or Sir Basil Spence’s concrete cubes at Trawsfynydd Nuclear Power Station.

Battersea Power Station on the other hand – once described as a ‘Temple of Power’ – was a world-class monument in the service of the people. It embodied the strength and power of British industry; it catered to one-fifth of London’s electricity needs and at a height of 370 feet, it didn’t so much look down on the capital, as watch over it.

As the twentieth century rolled on however, coal-burning stations like this gave way to a rise in gas and nuclear power; and in 1983 Battersea Power Station was finally shut down. Its generating capacity had decreased with age, while the cost of maintenance soared. No longer economically viable, the power station would be saved from demolition only by its status as a Grade II listed building… not that it made it any easier to work out what to do with the place.

For decades the station sat inert, as it slipped into an increasingly derelict state. Meanwhile, half a dozen redevelopment proposals came and went. Amongst them was the plan to turn the site into a theme park: the scheme received planning permission and large segments of the station’s roof were removed in preparation, though by 1989 the project was called off over funding problems. In 2008 there was even talk of Chelsea FC converting the site to a football stadium – but nothing ever came of that, either.

These two proposals had at least one thing in common: they would have offered an opportunity for the people of London to physically reconnect with the building that had become such an integral component of the urban landscape. These ideas were inclusive, and invited public participation with the space – but ultimately, they just weren’t cost effective. With London property prices climbing out of control, it would take a more aggressively capitalist approach to secure a guaranteed return on such an investment.

In 2012 Battersea Power Station was put on the open market, and subsequently bought up by a consortium backed by the Malaysian government and the world’s largest palm-oil producer. The building and its surroundings are to be thoroughly redeveloped, according to the architect’s vision, to create a new 40-acre urban ‘village’ fitted with restaurants, shops, office space and thousands of new homes… homes that will typically cost in the region of £1 million and upwards.

Inside the power station itself meanwhile, penthouse suites will go for as much as £30 million. The iconic chimneys are to be replaced with clean modern replicas. Prada and Burberry stores will both get floor space inside the station building, and already some are referring to the project as ‘Dubai-on-Thames.’

On 21st September 2013, the people of London were invited to take one last look inside Battersea Power Station; before the heavy machinery rolled in to commence an £8 billion redevelopment project. That open day attracted 18,000 people, many of whom reportedly queued for up to five hours before being ushered inside. I would have been there too, if I could – but on that particular date I was looking at a very different power station, on a tour of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine.

After that, I thought I’d missed my chance to ever see inside Battersea Power Station. I knew plenty of people who’d snuck in, back before all the attention that came with the Malaysian deal – during those three decades when it stood dark and abandoned. Now buzzing with the lights, life and security cameras of its latest billionaire owners though, for me it looked as though Battersea was always going to be ‘the one that got away.’

And then, this happened.

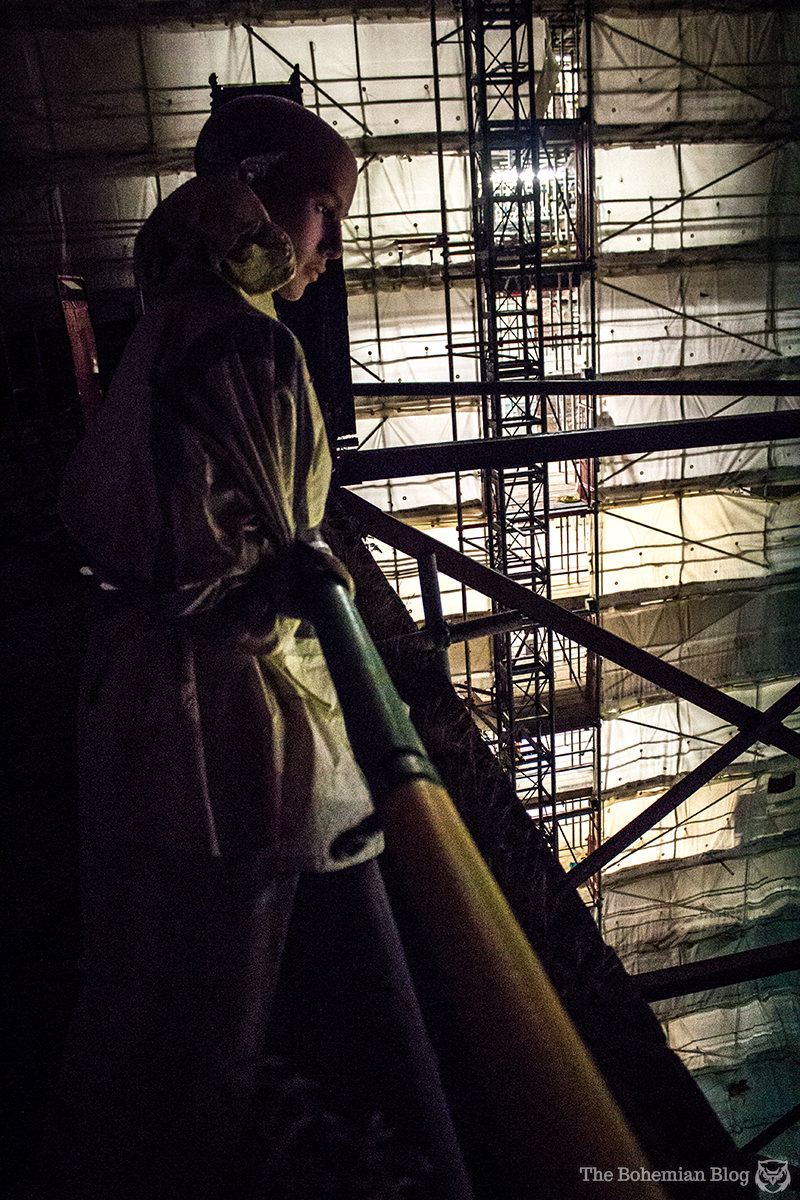

We arrived on the roof of the power station after dark. Two of our group had been inside Battersea before; but I wasn’t the only one who would be seeing all this for the very first time.

After climbing the scaffold staircase (floor after seemingly endless floor of it), the night air came as a welcome relief. I stepped out onto the asphalt roofing, flashlight at the ready – though I needn’t have bothered. The red lights tipping each of the nearby cranes bathed the rooftop in a peculiar, ruddy glow.

I crossed immediately to the inner barrier, the balcony overlooking the central space of the power station – my first ever glimpse inside the behemoth. It was like looking into a quarry: ladders and support structures zigzagging down the pit, a dark, gaping chasm hollowed out between walls of soot-stained brick. Tiles still clung to the faces of lower floors in pearlescent clumps. Tarpaulin hung from steel like pale snakeskin, while the ground beneath was a maze of pipes and girders, raw materials piled in stacks between the bulldozers and heavy machinery.

Somewhere far beneath us, inside the old turbine halls, the heavy engine noise of a generator rose into the night as it powered the countless spotlights hanging from bricks and scaffold bars. The place felt alive with energy… just not of its own making. How humiliating for Battersea – once ranked amongst the most efficient power stations in the world – that these days it couldn’t even power its own lightbulbs.

Beside me, peering over that same balcony, stood a stranger. It was a plastic mannequin, dressed up in a high-vis jacket and tethered to the railing. A scarecrow glaring down from the rooftop.

We didn’t linger long up there. The night was short, and we had a lot to see; so we made a line straight back to the stairs, and then down into A-Station in search of its cold, dead heart.

Battersea Power Station is formed from two near-identical halves that were built on either side of World War Two. The first of these, Battersea A Station, went into construction in 1929 and was generating electricity by 1933.

According to a 1937 issue of Wonders of World Engineering, the six boilers in Battersea’s A-Station were fed by furnaces that burned 17.5 tons of coal in a single hour. The three turbines could rotate at speeds of up to 1,500 revolutions per minute, and between them generated an electrical output of 243 million watts. The last turbine, installed in 1937, was the most powerful in Europe – running at 140,000 horsepower.

According to a 1937 issue of Wonders of World Engineering, the six boilers in Battersea’s A-Station were fed by furnaces that burned 17.5 tons of coal in a single hour. The three turbines could rotate at speeds of up to 1,500 revolutions per minute, and between them generated an electrical output of 243 million watts. The last turbine, installed in 1937, was the most powerful in Europe – running at 140,000 horsepower.

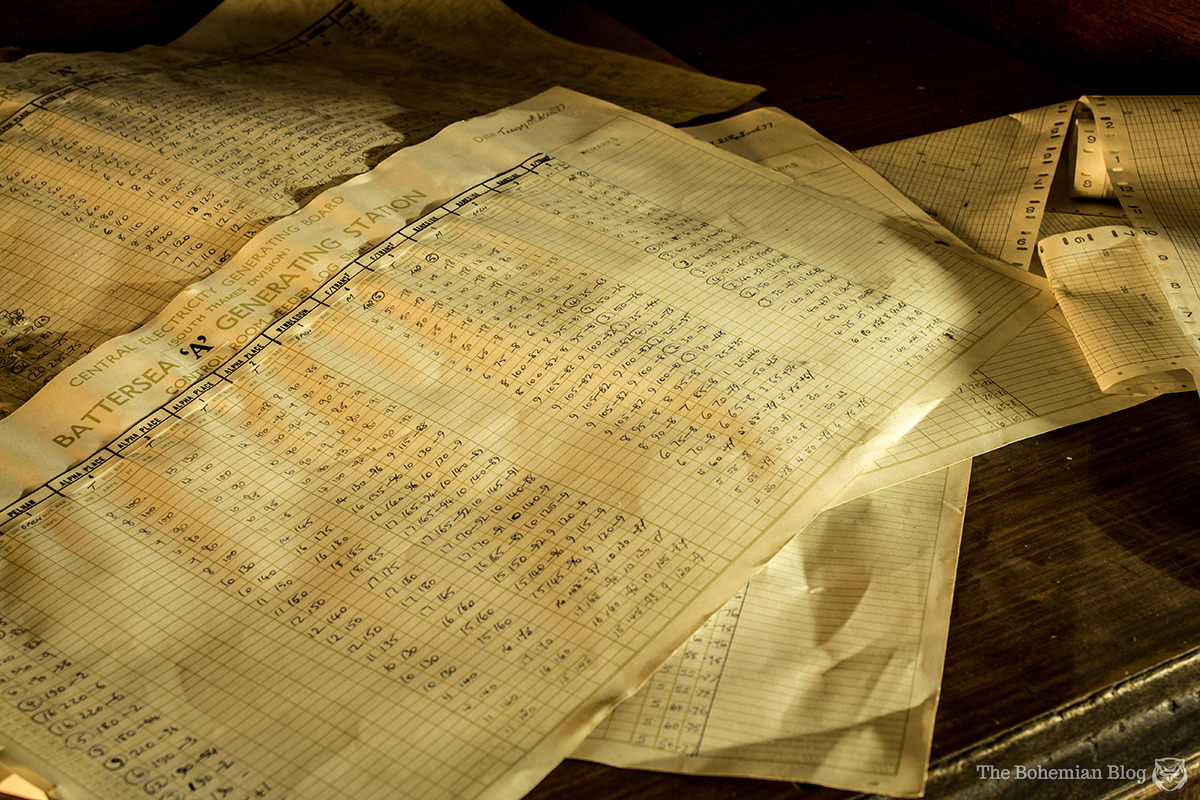

All of this machinery fed back into the power station’s nerve centre: a lavish Art Deco control room full of cranks and dials and gauges. Above the instrument panels, illuminated diagrammatic plans gave station officers a visual systems display – while engine telegraphs were installed so that orders could be transmitted directly from the control room to the turbine engineers down in the hall below.

Having always pictured the control room as the beating heart of the power station, I naively assumed that it would be easy to find; as if any path we took would lead us there eventually. I was wrong. We had more than a dozen floors to choose from on this A-side station block, each one the length of three Olympic swimming pools. More challenging still, most of the internal corridors were locked.

The A-Station turbine hall was filled with a scaffold frame, and so we started working our way down the bars. Layer after layer of steps and gantries, weaving our way through a three-dimensional industrial maze… until at last, we found the entrance.

If Control Room A felt somehow familiar, it was likely because this space has been so thoroughly embedded into the fabric of British culture over the decades; starring in music videos, and countless TV cameos from Sherlock to Monty Python. The lights inside were already burning bright, which only added to the surreal sense of welcome.

Time stopped as we explored the control room, its archaic dials and displays all crafted with the lavish decadence of a palace ballroom. The scale, complexity, and effect of the place is difficult to put into words… so instead, I’ll simply let these pictures speak for themselves.

After taking my fill of photos, I cracked open a pre-mixed gin and tonic – then drifted with it from one console to the next, playing with switches and dials. This control room was like nothing I’d ever seen.

When at last we all felt satisfied, we finished up in Control Room A and showed ourselves back out. It was time to go and repeat the process all over again, as we searched the opposite station for the famous ‘Switch Room B’… but before we could do that though, we would need to get across the wide open space of the turbine halls below.

Climbing down from the scaffold we eventually set foot on solid ground inside the gutted centre of Battersea A Station. Where once the turbine halls had featured floors of compressed mosaic, now we were walking through earth and mud, churned up into waves by the tracks of heavy machinery.

On the ground floor we passed beneath a couple of large wall-hangings, Art Deco prints suspended in alcoves several floors up. They looked almost authentic here, flanked between fluted columns, though I’d later read they’d been fitted for a party held sometime in the 1990s. More recently, the station floor doubled up as a warehouse for a scene in The Dark Knight.

On the ground floor we passed beneath a couple of large wall-hangings, Art Deco prints suspended in alcoves several floors up. They looked almost authentic here, flanked between fluted columns, though I’d later read they’d been fitted for a party held sometime in the 1990s. More recently, the station floor doubled up as a warehouse for a scene in The Dark Knight.

Before we left A-Station behind, we had a quick go at finding the ‘White Room’: a showroom built for the benefit of an earlier redevelopment project. The photos I’d seen showed a minimalist mock-up of a luxury flat – double bed, lots of mirrors and a tiled hot tub – all decorated in sterile white and hidden away down some dark corridor in the rusty bowels of Battersea. We seemed to be getting close to it; until we met a series of corridors plastic wrapped for fumigation, someone said asbestos, and I think we all just decided against pursuing it.

Instead we headed over to B-Station – crossing the open, floodlit space of the turbine halls, an area that my comrades referred to as ‘No Man’s Land.’

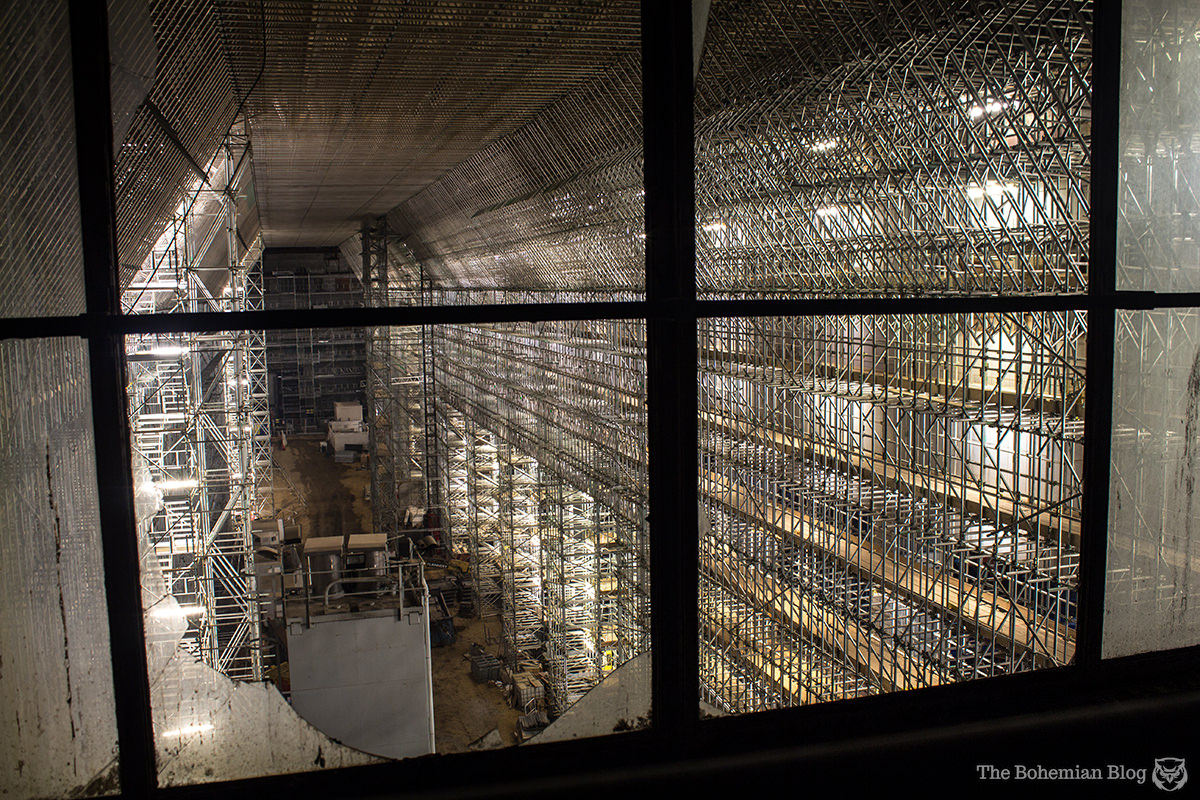

From A-side we passed under brickwork arches, and stepped out into some kind of space-age cathedral. An intricate skeleton of steel bars lined every inch of the B-Station turbine hall, lit by hidden spotlights and rumbling with the bassy thunder of industrial generators.

From A-side we passed under brickwork arches, and stepped out into some kind of space-age cathedral. An intricate skeleton of steel bars lined every inch of the B-Station turbine hall, lit by hidden spotlights and rumbling with the bassy thunder of industrial generators.

Mesmerising as it was, we tried not to linger in No Man’s Land; heading instead for the scaffold at the station’s eastern wall, scrambling up the bars until we were able to melt back into the shadows of a recessed gantry. Soon we had disappeared inside the old fabric of the station itself, into an industrial labyrinth of corridors and pipes. We climbed, one floor after another, mirroring our ascent of the A-Station – until eventually we squeezed past a wire-mesh gate, through a dark corridor heavy with the acidic stench of birdshit, and from there into Switch Room B.

Battersea B Station was brought online between 1953 and 1955. The power station’s second phase had always been intended to duplicate the first; but by the end of WWII the UK’s electricity supply had been nationalised, and the post-war budget simply didn’t allow for the same Italian marble and Art Deco stylings.

Instead, the interiors of B-Station received a different treatment altogether. Staircases and corridors were decked out in minimalist grey-white tiles, while its nerve centres were fitted with slick stainless steel consoles. At the time it probably looked futuristic; though now it conjures images of a B-movie sci-fi film set, the era of flying saucers and ray guns.

I had seen it in pictures before, and had always assumed this place served as the B-side control room: though my learned colleagues told me otherwise. Its official designation was ‘Switch Room B.’ The real Control Room B had been located on the floor immediately above, but was stripped out in the late 1980s; there wasn’t anything to see there now.

I flicked some switches, cranked some levers – they moved with a satisfying thunk – then brushed the dust from a silvery display panel. Though neither as large nor as grand as Control Room A, this space had its own unique ambience; while these two brains, taken together, made for a fascinating comparison. Each seemed so perfect for its time… yet what a radical change in design they marked for a period of just two decades.

In the corner of the switch room I lifted a sheet of tarpaulin to find yet another bank of gauges and dials. Meanwhile the two free-standing ‘synchroscopes,’ with their anthropomorphic faces, watched us like a pair of sad robots.

Back down in No Man’s Land, as we had run the gauntlet from one hidden corner to the next, one of our group had spotted something interesting on a higher wall. It was a balcony that jutted out from the tilework perhaps some eight-or-so floors above us, a windowed observation deck overlooking the length of the B-Station turbine hall.

We’d passed it by in our hurry to get to Switch Room B; but now, roughly four hours in and with two of our main targets already under our belts, we decided to investigate.

We’d passed it by in our hurry to get to Switch Room B; but now, roughly four hours in and with two of our main targets already under our belts, we decided to investigate.

Getting up there proved easier said than done, however.

Through the tiled corridors we went, into the eastern block of the power station. These opened up soon into halls and girder-lined chambers, great big spaces that felt like warehouses or underground car parks. Pipes ran this way and that through the semi-darkness. We followed the stairs up through more levels of the same, until we reached an area already in the process of redevelopment.

On these higher floors a new infrastructure had been juxtaposed against and between the old walls, scaffold bars threaded through every possible space. New floors of stamped steel sliced through the headroom, segmenting each level into smaller strata. The higher we climbed, the harder it became to move – ducking beneath low ceilings while hopping over, or under, the poles that cut our path – and when someone pointed out what looked like asbestos sheeting up ahead, we decided to give up. Back down into the bowels of B-side we went, to start from the ground up in search of another route.

Behind the bulldozer, across a treacherous stack of slippery pipes, we made for a scaffold staircase set into the northern end of the station. Maybe half a dozen floors up, the stairs folded around into a long, pillared gallery overlooking the River Thames: a space reserved for future penthouse flats.

At the far end a sheet of plastic hung in place of a collapsed wall – and ducking under, onto tiled steps perched precariously high above the turbine floor, we followed the ledge around and into Auxiliary Control Room B.

This room had contained a copy of the main B-side control room, and served as a back-up control suite for B-Station. Not that there was any evidence for it left. This auxiliary control room was converted to office space in the mid-1960s, its equipment was removed and now there was nothing to see but tiles and broken glass. Set in the north wall, a small window looked down across the Thames to the lights of residential blocks on the far bank: a view now valued at £30 million.

This room had contained a copy of the main B-side control room, and served as a back-up control suite for B-Station. Not that there was any evidence for it left. This auxiliary control room was converted to office space in the mid-1960s, its equipment was removed and now there was nothing to see but tiles and broken glass. Set in the north wall, a small window looked down across the Thames to the lights of residential blocks on the far bank: a view now valued at £30 million.

It was the southern aspect that interested me, though. Through the shattered glass of the observation window, the B-Station turbine hall fell away like some great steel-ribbed tomb. Its dimensions, the radiant light that flooded it, felt anything but accidental – more like sacred architecture than the byproduct of some mundane construction process.

It was hard to believe that such sights could exist in secret, hidden away here with no intention of it being seen or appreciated by anyone. We drank in the view until we were heady with it; and then we made our way up to the chimneys.

By the time we got back to the rooftop, it wasn’t that long before dawn. Those labyrinthine staircases were such a challenge to navigate that we ended up getting lost on the way – at one point finding ourselves walking over the scaffold roof at the very top of the A-Station turbine hall, a 160-foot drop just visible between the bars under our feet.

We crossed the rooftop, through puddles of rainwater illuminated by the cranes’ red light; and reached the inner edge, where the familiar scarecrow waited like an old friend. Above us, four pale chimneys reared up into the night sky.

It’s easy to take these chimneys for granted, when you’re so used to seeing them up there on the London skyline; but experienced this close, they really are quite enormous. At 28 feet in diameter, each chimney is large enough that it could be turned on its side to create a new tube station, with space inside for tracks and trains and platform.

We headed for the southwest corner: to the new chimney, recently erected after the 2015 removal of the oldest – and most decayed – of the four. I have to admit, I could barely tell it apart from the others. The problem however, I thought as we climbed, was that these new chimneys would never have known the purpose of the building to which they were attached. The chimneys they’re raising now are a visual gimmick, for branding purposes only; a familiar symbol to justify the price tag.

We ascended the southwest tower from inside, at first, before following the stairs back out; onto the scaffold that wrapped itself around the exterior of the stack. Moving under the skin of the tower, beneath red-lit canvas that crackled in the wind, we rose high above the roof of Battersea A-Station.

At the top of the stack, where square red brick gave way to cylindrical concrete, we came to a dead-end. The hatch above us was locked: the final access to the chimney itself, bolted shut. It was as far as we were going to get tonight, so we settled here to appreciate the view… looking out across the power station to the half-built shells of the surrounding residential blocks, to the River Thames at their feet, and the city of London beyond that.

One day, I thought, all this will be deposit boxes: the empty flats of foreign investors, riding the tide of London’s property market. There’ll be exclusive boutiques laid out like supermarket aisles around the tethered titan; the power station itself, a taxidermy in brick and glass and steel, a monument no longer dedicated to the People but to black gold and palm-oil.

I’m just really glad I got to see it before any of that could happen.

Comments are closed.

An illustrated guide to urban exploration in the Russian capital.

Poltergeists, ritual murder & a live-in succubus – the 1000-year-old pub with a ghostly reputation

A month-long monument hunt, and what I learned along the way.

I was an Operations Engineer from 1957 to 1983 in BPS, the highlight of my working life.

Control Room B seems to me to be a cross between the machinery on the movie Metropolis and the works of the Krel on Forbidden plane! I hope they keep all those control rooms intact as museums. Or at least not scrap the equipment – there are many people who would love to have some of those items. A real work of engineering beauty. Would like to have seen the whole thing. … Have you more photos or videos?

Had the pleasure of working in this iconic building in the late eighties, wont forget it in a hurry.

Is it easy to access now? I was planning to go next week but I don’t want to travel that far if i can’t get in… thanks!!

It was very hard to go inside when I visited, and it’s impossible now – the apartments have been built, and many are already sold. I’m glad I saw this when I did, but unfortunately, it just wouldn’t look like this anymore.

You’re a terrific writer! The adventures are so engrossing. Keep it up!

Thank you, Tom – that means a lot.

Is it still possible to gain access to the battersea power station? I’m in London in march and would love to check it out

Hi Ben. It seems unlikely – the construction project is moving on quite fast, and visitors are not welcome. But saying that, we still managed…

What a well researched report on your adventure, I didn’t know much of Battersea’s history but you’ve included some great details. I’d have thought if JG Ballard were alive he’d have written about how close this building has become to his own imagery created in High-Rise.

Yes, there is something very Ballardian about the concept, isn’t there? I wonder how it’ll all turn out there. Anyway, thanks for the comment Tim!

You’re photographs are stunning. It looks like a really beautiful place there. God I’d love to go and take some of my own photos… Mesmerizing…

Thank you so much! It’s a super photogenic place – really fun to explore with a camera. You’d love it. Maybe you’ll get there yet…!

So it’s still worth doing? I assumed that time had long gone.

Yeah, I had assumed the same thing. As it turns out though, it’s definitely still worth a visit.

Epic. Just epic. Friggin love the photography…

Cheers Ken. To be honest, it was kind of difficult to take a bad photo of the place…

Fantastic post! Am unbelievably jealous you got in. Love reading your blog.

Thanks a lot, Andrea. Glad you enjoyed this one!