MiGs, Stars & Magic Books: A Brief History of Trespassing in Moscow

An illustrated guide to urban exploration in the Russian capital.

1 February 2023

Interhotel Veliko Turnovo was once amongst the premier tourism destinations in Bulgaria. After decades of decline however, it finally closed its doors during the pandemic, when the company that owned it filed for bankruptcy. Its future now is uncertain… but it doesn’t look promising. I was a regular visitor during the last decade of the hotel’s life, and subsequently this feels something like a eulogy – both a reflection on fond memories, and a lament for the downfall of one of my favourite works of architecture.

Nikola Nikolov came from Nova Zagora, a small town on the south side of the mountains.

After studying architecture in Sofia he spent a decade in apprenticeships before starting his own independent practice in 1957. His first subsequent work was as chief architect of the Slunchev Briag (‘Sunny Beach’) resort, but he would also work on the restoration of the medieval architecture of Nessebar, and urban plans for the centres of Sofia and Veliko Turnovo. Nikolov made monuments too.

In Ruse, he would design the (1978) Pantheon of Revivalists – a memorial-ossuary commemorating the nation’s heroes and containing the bones of 39 of them. An older church was demolished to make room for Nikolov’s pantheon, and his design seemed to reference the former place of worship – a marble cube full of solemn spaces, statues and art, and topped with an Orthodox-style golden dome. So much did this pantheon resemble a church, that in the post-socialist period the site was “re-Christianised” simply by attaching a cross to the top of Nikolov’s dome. He worked with human remains again in Sofia, for his (1980) Monument to the Unknown Soldier. This memorial tomb was subtly subversive for its day – it commemorated all Bulgarian warriors who fell in defence of the Fatherland, but crucially, it did not specify particular dates or conflicts. In these years, Bulgaria was in a complicated relationship with the domineering Soviet Union, and Moscow preferred its friends to memorialise only their heroes who had fought alongside Russia in the past; whereas a monument to all fallen warriors necessarily included even those Bulgarians who had taken up arms against Russia in WWI.

All this time however, Nikolov was working on something bigger. He had been 45 years old when he got the commission to design a new riverside hotel for Veliko Turnovo, Bulgaria’s old medieval capital. A national contest was called in 1967, and his entry was selected by the jury – though it would take 14 years to see it to completion. Nikolov would later write:

“I started working on this site without thinking much about it. It fascinated me. When I realised that it was a difficult task due to the terrain of the surrounding existing buildings and woody vegetation along the picturesque braided Yantra river, it was too late to go back. I had joined the dance and it was not easy to back out” (Korespondent BG / SOS Brutalism).

The hotel was to occupy a position on the steep outer curve of the river, where the older houses, arranged in tightly ascending streets, rise so sharply up the hill that from the opposite bank they appear almost as if stacked on top of one another. This view, beloved by Bulgarians and tourists alike, reveals an urban plan entirely dictated by nature, a town clinging to the contours of the Yantra river valley. Adding a modern new hotel, equipped with 188 guest rooms, 8 halls and a swimming pool, to this postcard-perfect landscape of limestone and landslides, was both an engineering challenge, and a significant aesthetic one too.

Nikolov concluded that “the spatial solution is sought not in height but longitudinally,” and his design would strive to build organically into its surroundings: “with picturesquely dissected volumes to the river bank. Opportunities for the perception of the river and the architectural panorama of Veliko Turnovo, I designed with courtyards, terraces, and the original balconies of the rooms.”

They blasted into the limestone to lay foundations, and where the land fell away beneath the hotel, the riverfront side would be propped up on legs of reinforced concrete. There was a 20-metre difference in height between the front and back sides of the hotel, so that entering the lobby on the ground floor, guests would descend to a lower level to emerge on the riverfront patio. Stylistically, the hotel aimed to complement rather than match the pre-existing architecture of Veliko Turnovo. It was square and modern, but added cylindrical vertical elements reminiscent of medieval castle towers; while the curved shelters above the riverside patio resembled roof tiles, the old type that Bulgarian craftsmen would make from clay and straw, massaged into shape over their knees and then baked in the sun. The hotel was aligned north-south beside the Yantra, and at either end, the northern- and southern-most masses were capped with symbolic decorative crowns, like chess pieces, a king and queen for the Old Capital.

Interhotel Veliko Turnovo opened in 1981. It had been a long and difficult construction process, largely due to the challenges of the terrain, but additionally complicated when the project’s parent company, Balkantourist (Bulgaria’s state-owned tour operator since 1948), transferred management to Interhotel in 1978.

Tourism was a major economy for the Bulgarian state, and during the socialist era this was a highly popular destination for Soviet tourists (in addition to significant numbers from Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary). In 1977, the Bulgarian press announced:

“Thousands of meetings of [Bulgarian] and Soviet people along the tourist routes of both countries are one of the real forms of Bulgarian-Soviet friendship.” In that year, they stated, the national companies Balkanturist and Interhotel had between them “welcomed and served more than 160,000 Soviet tourists who traveled around our country on more than 25 different routes” (socbg.com).

Since 1966, the Bulgarian Tourist Union had been promoting its ‘100 Tourist Sites of Bulgaria’ campaign, and many of the sites listed would have nearby accommodation and hospitalities on offer courtesy of Interhotel. Tsarevets, the medieval fortress at Veliko Turnovo, was renovated between 1930 and 1981, being completed in time for the celebrations marking the 1300-year anniversary of the establishment of the first Bulgarian state. The same year the renovated fortress was added to the national tourism list, Interhotel Veliko Turnovo opened its doors to welcome tourists; though as part of the premier state-owned hotel network, it would also accommodate visiting diplomats, party officials or important foreign delegations to the Old Capital.

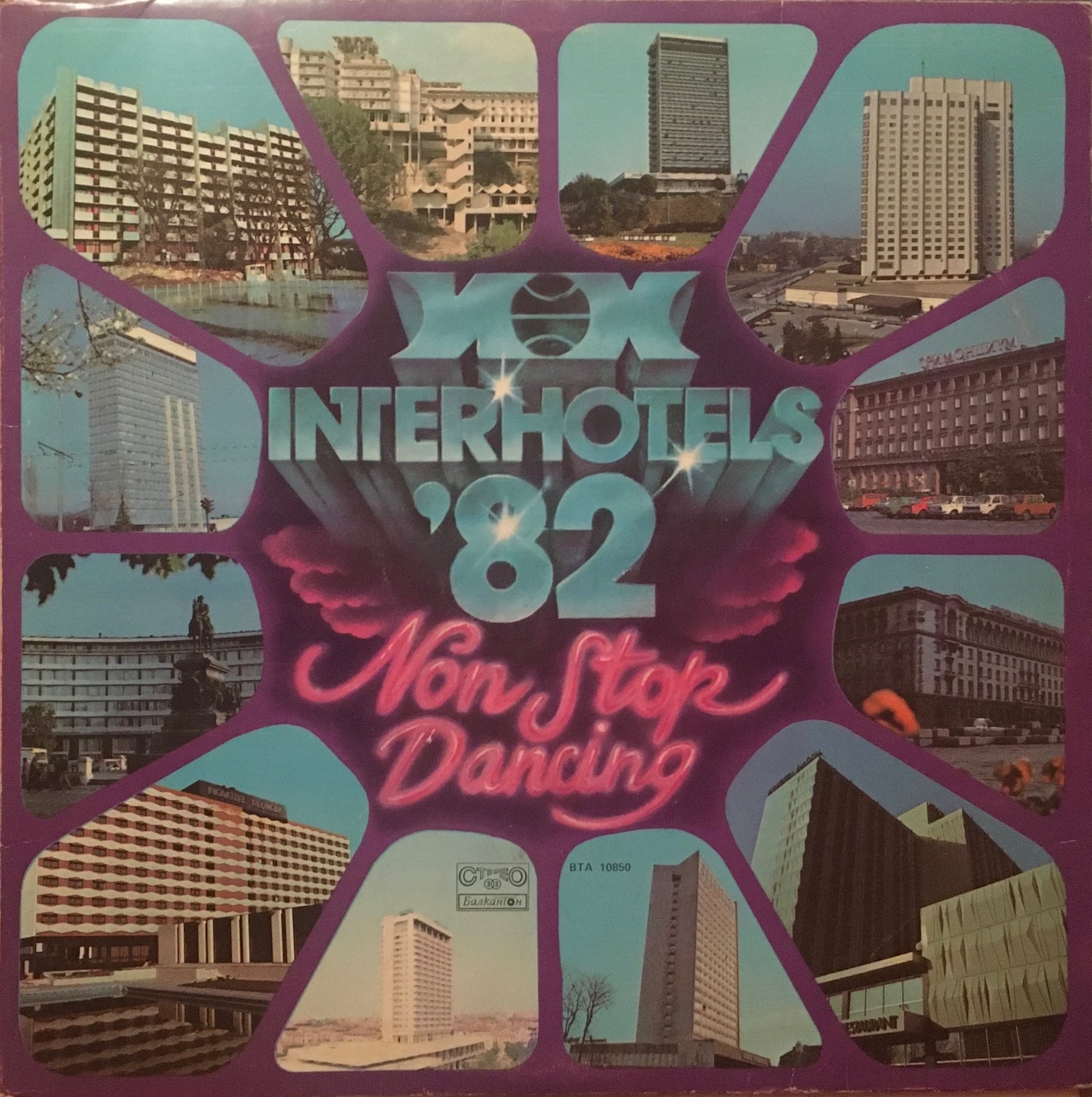

The hotel was considered a design marvel at the time, and in addition to its extraordinary architecture it featured lavish interiors decorated in frescos and tapestries, with works from Bulgarian artists including Boyan Brakalov, Petko Petkov, Stefka Koleva, and Ana Tuzsuzova (SOS Brutalism). In promotion of their hotels, during the 1980s, the Interhotel chain released a series of vinyl LPs on the state-owned Balkanton label, with Interhotel Veliko Turnovo appearing on the cover of Interhotels ’82: Non-Stop Dancing.

After the Changes of 1989, and the beginning of the dismantling of the socialist state, Interhotel Veliko Turnovo was privatised in the 1990s. For a while it became the property of Multigroup, a business conglomerate founded by the professional wrestler-turned-tycoon Iliya Pavlov, who by 2002 was ranked the “eighth richest man in Central and Eastern Europe” (according to Wprost). Pavlov was also alleged to be a mafia boss. He was looked at, though never charged, in relation to several high-profile assassinations, and a failed attempt on his own life in 1997 – a car bomb – left behind a crater seven metres long and three metres deep. A subsequent attempt in 2003 was more successful – a sniper shot him through the heart with a single bullet, outside his office in Sofia (RefWorld / Novinite). After Pavlov’s death, Multigroup sold the hotel to another businessman, Georgi Georgiev, who ran it from the 2000s onwards.

The hotel was stagnating though, in a state of gradual decline. A 1-star TripAdvisor review from a 2005 visitor reads:

“The people everywhere EXCEPT at this hotel were warm, kind and friendly. This hotel was AWFUL. The service was rude […] The room was dirty […] there was no air conditioning, no fans and no screens on the doors […] without screens, the doors being open at night was an invitation for the bugs and bats (yes, bats) to come in and join the party. To save energy, the hotel has all the hallway lights on sensors – a good idea in theory however, they came on when you were in line with the sensor, but they went off before you could even get your door open so you were left standing in the dark. […] All in all, it was the darkest dingiest hotel room I have ever stayed in anywhere in the world! I recommend the hotel for the view but, I personally would NEVER stay there again!”

From there things only got worse. Over the next decade reviews like this grew more common, while the hotel’s guests gradually grew fewer.

The first time I visited Veliko Turnovo, in 2007, I was immediately aware of the hotel – it’s impossible to miss. Back then, visiting the Old Capital with Bulgarian friends, it was introduced to me as an unfortunate eyesore. They thought it spoiled the view. I wasn’t so sure though. The hotel was clearly in need of maintenance, its pastel yellow exterior was stained and already then it projected a sad aura of decline; but the shape and scale of it fascinated me, and I liked the way it seemed to nod to the style of the older buildings around it, with its imitation of terraces and tiles. To me it seemed to complement, rather than contradict, its setting… but it looked badly in need of love, and maybe a fresh coat of paint.

It was inevitable that when I started leading architectural heritage tours in Bulgaria, from 2015 onwards, I would take my groups to stay at Interhotel Veliko Turnovo. As a result, I began getting to know the interiors of the building too.

The lobby felt too big. Beyond the seating areas that sat immediately alongside the reception, there was a bar serving cocktails and coffees, then past that, pool tables and a piano. On the carpark side of the lobby, away from the river, the space was divided into a series of (usually unstaffed) shops selling souvenirs, glasswares, fashion accessories and traditional Bulgarian costumes. At the end of a dividing wall that went down the middle of the lobby (and prevented this space from feeling even bigger than it already did), a staircase led down into the floor, to the breakfast and function halls beneath, which opened onto the lower patio on the river side. Back then, the walls were painted dark red in between exposed wooden panelling, giving this space a cavernous and organic feel, like the inside of a whale.

Hanging on the wall behind the reception desk was an oil painting of the hotel. It felt somehow wrong though, as if the artist had misunderstood the building – shoehorning this vast, angular hotel into a romantic-styled landscape, when really, something more modern, more constructivist, might have captured its personality more accurately.

Back then, there were usually two women working on the reception, and there was a curious ritual at check-in – the unexpectedly complex process of telling the guests how to get to their rooms. Two banks of elevators ascended from the lobby, one around the corner from the reception desk and the other directly across from it. However, different lifts stopped at different floors. Guests staying on Floor 3 had to take one elevator, guests on Floor 4 and above took a different one. Guests on Floor 2 followed a long corridor from the lobby, where after a while room numbers would suddenly jump from the 100s to the 200s. Or something like that, I forget exactly – the hotel had a quirky numbering system, a surprisingly confusing layout, and it consistently confused me over the years.

Sometimes we would get rooms just above the lobby, in the centre of the building and looking towards the river – these all had long, thin balconies that resembled diving boards. More often, we’d end up in the southern wing of the building, where the last part of the corridor was an area behind a dividing door, with its own seats, tables and potted plants. That was a good place to stay with groups as it felt like we had our own little private lounge. We never got booked into the north wing though – no one seemed to stay there, and the lights were usually switched off.

I rarely used the elevators, preferring to walk and see more of the building. Corridors stretched the length of the hotel, framed between rows of wooden doors, and past tall windows which in summer were opened, so that their full-length curtains would flap and flutter in the wind. It was always dark inside – pitch black at night, with automatic lights that flickered on as you passed them (but always a little later than would have been helpful), so that either end of the corridor, ahead and behind you, would disappear into blackness.

There was something liminal and uncanny about it, a perpetual sense of having arrived thirty years too late for the party. The Mary Celeste in hotel form. Driving tour groups to Veliko Turnovo on the minibus, when guests asked what the next hotel was like, the easiest way to put it was: Imagine a post-socialist version of The Shining…

We rarely saw other guests at the hotel – the odd couple or family, sometimes. Once there was an athletics team from out of town, their bus parked outside, and all of them sat in matching tracksuits around the lobby. Another time, I went down for breakfast and there was an American couple sat at the next table across. I’d barely buttered my toast before they started talking to me about religion – they were missionaries, they explained, here on church business, and they were anxious to know if I had accepted the Lord Jesus Christ as my personal Saviour.

Another time there was an end-of-school ceremony being held downstairs in the conference space opposite the breakfast hall. These weren’t guests – they were local students in smart suits and dresses, and they filled the lobby all morning, posing for photos against backdrops of marble and wood. It felt like a tiny glimpse of what this place must have been like in its glory days.

We always wondered how the hotel actually worked as a business. The number of guests we encountered didn’t seem nearly enough to cover the costs of staff and maintenance. One guest theorised it was being run at a deliberate loss, a front for money laundering.

I had a guest from Berlin, another time, who was a tour guide himself – and he had a particular knowledge of the socialist architecture of the DDR. While walking along a corridor on the third, maybe fourth floor of Interhotel Veliko Turnovo, he pointed me to a door marked “Laundry,” and asked Why would you put the laundry at the top of the building? Laundry facilities would usually be on the ground floor, or in the basement. In East Berlin, he told me, hotels for foreign guests would sometimes have a “listening room,” where security staff could monitor the bugs (like this one) in the guest rooms. Important foreign guests, journalists or politicians, might find themselves staying in the upper floors of a hotel right next to a small room labelled something innocuous like “Laundry.”

Whatever secrets the hotel might once have guarded though, seemed like a long time ago. Interhotel Veliko Turnovo felt almost abandoned at night, the lobby empty and the doors to staff areas left hanging open. There was one night when we finished dinner but I wasn’t tired, so I decided to take my camera and find a view of the city. I followed the staircase up the southern wing, each new floor in darkness until I took a few steps onto the carpet, and the lights came on. When I reached the top of the stairs there was no light at all – just a dark landing and a single door that stood ajar.

It led to the service room containing the elevator winch. Inside, around the machinery, stood dusty stacks of boxes, crates, spare tables and chairs, all lit orange by the streetlight glow coming in through the windows. Some of those windows were broken, all the glass gone. These gaping holes led straight out onto a flat roof, and from there, a ladder extended up inside the concrete crown above the southern wing – meaning there was not so much as a closed door all the way from the hotel lobby to the very highest part of its rooftop. I got my city view alright.

During these years I was doing a regular tour circuit in multiple countries, and getting to know some hotels (and their staff) particularly well. I stayed maybe a dozen nights each year in Hotel Salyut in Kyiv, and another dozen at Hotel Jugoslavija in Belgrade. At Hotel Rila, in Sofia, by this point I was on first-name terms with both the manager and the architect. But in contrast, Interhotel Veliko Turnovo always felt distant and impersonal. I made bookings by email with someone I never met – and the onsite staff never acknowledged if they recognised me, even from one month to the next.

The Interhotel was more than just a place to stay with groups. On these architecture-themed tours, it became a highlight of the itinerary. One time we were checked in by early afternoon, and the rest of the day was scheduled for free time exploring Veliko Turnovo. I gave the guests a map of things to see and do around the city, but one of them nodded instead towards the lobby bar, and asked, Are they open?

At that time the bar was still staffed – so we got cocktails, and took them with us as we wandered the quiet corridors, or sat chatting on scenic balconies. By dusk we regrouped on the patio, glasses recharged, and watched the city lights illuminate across the valley. I don’t think one single guest left the hotel that evening, and later, some called it the best experience they’d had all week. Even despite the creeping decline, it was simply a well-designed space that felt good to be in.

Later, that September, a few of us sat to eat dinner on the wooden patio outside the hotel’s riverside mehana (a traditional-style tavern). From here there was a small staircase disappearing down towards the water, and between courses, we followed it – braving the mosquitoes – onto a path that led through the undergrowth, and right in amongst the concrete supports of the hotel. The space beneath felt like a cave looking out across the river, where frogs and insects nested amongst the damp foundations, and with all the psychic weight of the hotel pressing down from above.

Sometime around 2018 the lobby got refurbished. The dark red paint was replaced with inoffensive magnolia; indented wooden panelling was hidden behind clean, plasticky laminate. The lobby began to feel less like a cavern, and more like an airport terminal. The café-style seating near the pool tables was pulled out, leaving a huge open space.

New art went up too – a surreal collection of paintings that reminded me of H.R. Giger, or Gottfried Helnwein, all conjoined black figures with weird limbs and mismatched parts, abstract images that seemed to imply some kind of body horror. It was a strange choice for a family hotel.

The lobby now had a “business centre” too – an illuminated glass cubicle under the stairs, with a small desk, a PC and a printer. (Though the one time I asked to use it, to print tickets, I was told it was temporarily unavailable.)

The refurbishment didn’t seem to extend beyond the lobby though. Upstairs little had changed, only a slow and constant deterioration. The refurbished foyer wasn’t the new lease of life it initially resembled, but rather, more likely a final attempt to market the hotel to potential buyers. And now it was run by a skeleton crew. On my earliest visits there had been multiple reception staff, a lobby barman, cleaners patrolling the corridors and then separate teams who managed the mehana, or came in the morning to run the breakfast service. By 2018, both the bar and the mehana appeared to be permanently closed, and some of the rooms didn’t look like they had been cleaned in a while – there was grit in the carpets, and you might find a sock under the corner of your bed, or a used ashtray on the windowsill. The receptionist disappeared into the office after checking us in, and then we sometimes saw no one else until breakfast, where one single woman appeared to be heating the buffet food, serving it, then clearing tables after. The coffee was bitter and oily, squeezed out of a machine into little china cups.

The last time I took a group there was in December 2018. By this stage it was normal for me to warn groups in advance that this would be an interesting night, but not necessarily a comfortable one. The guest rooms might be missing toilet paper, or soap, or towels. The pipes made strange noises, and some mornings you had to run the taps for a while before you found hot water. We would make a joke out of it though, and I usually booked somewhere extra comfortable the following night to compensate. Most guests still thought it was worth it, for the history and the architecture. But by winter 2018, the hotel had deteriorated to the point that staying there felt like camping in an abandoned building.

That week the first snowfall had just begun to settle, and the nights had grown bitterly cold. At Interhotel Veliko Turnovo, we soon found there was no heating in our rooms. I went to the reception desk, where the stern woman on duty clicked her tongue in irritation, then offered us an electric heater each. That sounded like an acceptable solution… until we lugged those heaters back up to our rooms, only to find that half of us didn’t have working electrical sockets to plug them into. Back at reception again, this time she offered us extra blankets: heavy rolls of bedding that smelled of damp storerooms. There was no internet, no hot water, and a breakfast that tasted like canned food warmed up in a microwave.

It had gone too far now, and I couldn’t, in good conscience, take paying guests to stay there anymore. But that didn’t mean I stopped staying there myself.

When I took tour groups through Veliko Turnovo in 2019, we stayed at a different socialist-era hotel – but one which had been renovated almost beyond recognition now, with modern furnishings, friendly, bright-eyed staff and an espresso machine in every guest room. We still visited the Interhotel though. We stood outside where I showed them photos, and talked about the construction process. When the staff allowed it we took a quick walk through the lobby and patio too. But I found it a sad place to visit now, having got to know it, then watched it fall apart.

The last time I stayed there myself was in October 2019. Two Ukrainian friends came to visit me in Bulgaria and we made a small road trip around the country. At Veliko Turnovo, we stayed in the Interhotel. The weather was still mild, and we brought our own drinking water, soap and hand wipes, the sort of things you’d pack for a camping trip. After check-in and finding our rooms, we regrouped to explore the hotel. I think we must have been the only guests in the building, as we drifted from one floor to the next, along corridors, through lounges, up and down service stairwells. One of my friends commented that even compared to Ukraine’s post-Soviet relics, this was an uncommonly shitty hotel. He said it matter-of-factly, and with a nod of refined appreciation as if he was praising an uncommonly peaty Scotch.

We ended up in the north wing that night. One corridor, at right angles to the main body of the hotel, was spacious enough that a smaller hotel might have labelled it a “hall.” Assorted couches and floor-length curtains broke up one long wall, while opposite, a row of open doors revealed empty guest rooms with bare mattresses. The lights in this part of the hotel didn’t come on at all. It felt so bizarre and contradictory, this grandly oversized holiday palace, now empty, kept alive on life support alone, seemingly for the benefit of no one.

And that would be the last time I set foot inside the building.

The pandemic was murder for the tourism industry. Bulgaria closed its borders, and at the worst point, you couldn’t even travel from one city to the next without some kind of justification. Hotel Rila in Sofia began letting out rooms as office space, while numerous other properties simply starved to death after the tourists stopped coming. After that stay in October 2019, I didn’t get back to Veliko Turnovo again until 2021 – and by then the Interhotel was well and truly dead.

The glass doors at the entrance were locked, and the lights inside were turned off. Across the door were posted a series of legal documents, court summons for bankruptcy proceedings, addressed to the hotel’s owners, but seemingly unanswered. The car park was empty and the paper notices flapped sadly in the breeze.

I realised then that I had never properly photographed the hotel. I had snapped various photos over the years, whenever I happened to have a camera in my hand – but I had never once taken out my tripod, or made any real effort to document the halls, the corridors, the guest rooms. I got so used to staying there, I just always felt like there would be another opportunity in future.

As we walked around the end of the hotel, something moved in the courtyard below. I glanced down to see an older-middle aged man in a plain uniform looking back up at me with a steady gaze. Behind him, a new guard booth had been installed and security signs were pinned around the sealed entrances. The man said nothing, but kept his eyes on us until we left.

In 2022, the first “urban exploration” reports from Interhotel Veliko Turnovo started popping up on the internet. They were by local Bulgarian photographers who had snuck in, past the guards. It was strange to think that the abandoned building in their shots looked basically the same as it had when I was still paying to stay there.

The landscape of Bulgaria is changing. Since I started running tours in 2015, there are various places we used to visit which became inaccessible over the years. The Buzludzha Memorial House, and the Monument to the Bulgarian-Soviet Friendship at Varna, were both once left wide open, with stairs going all the way up inside to rooftop balconies – but at present, neither can be entered. Meanwhile the Monument to 1300 Years of Bulgaria, in front of the National Palace of Culture in Sofia, was demolished in 2017, so that now we visit a plain grass lawn and I show tourists photos of what once stood there. Interhotel Veliko Turnovo seems now to be heading in the same direction.

Throughout 2022, several attempts were made to sell the hotel. It was reported that the hotel was previously offered for sale in 2014, passing in October 2015 to the joint-stock company Interhotels AD, based in Pleven (SOS Brutalism). In 2020 it went up for sale again, at almost 25 million levs (around 12.7 million euros) – but no one came to the auction. The starting price was dropped to 20 million levs, but there was still no interest. That October the price dropped again to 17 million levs, but it still wouldn’t sell (Dnes BG, June 2022).

After Interhotels AD was declared bankrupt, in July 2022 the company liquidators put the hotel complex up for sale again – this time at the significantly reduced price of 12.4 million levs. Another attempt in October 2022 reduced the price 5%, to 11.8 million levs, or around 6 million euros (Dnes BG, September 2022). I haven’t seen any updates since then, and for now at least the hotel remains unsold.

At this stage it is hard to imagine the hotel ever “bouncing back” under new management. The complex currently costs six million euros – and after that, the first task of any prospective new hotelier would be to conduct a thorough survey of the building and its foundations, and likely, by this point, make extensive refurbishments and repairs. As the building visibly degrades year after year, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to argue with those locals who already considered it an eyesore. But even just to demolish the hotel and build something new (as some have suggested), would be an incredibly difficult and expensive project.

You could call it a victim of the pandemic, or a victim of mis-management, but I think the problem goes deeper – Interhotel Veliko Turnovo is a victim of the Changes, a hotel built for one type of society that never quite found its purpose in the next. It simply wasn’t designed to exist outside the scaffold of state-managed tourism, or without the state’s budget for maintaining it. Most tourists don’t come to Veliko Turnovo looking for modernity anyway; so when placed in direct competition with a hundred cosy boutique hotels, all with that same view, the Interhotel never stood a chance. The non-stop dancing finally stopped. Its death was inevitable, and it seems as though its corpse may still linger on in some form for a while yet.

So it seems I may have spoken too soon. Interhotel Veliko Turnovo went up for auction again, a few days before Easter 2023. This time the hotel was actually sold though – to the only bidder, the local businessman Velichko Minev. Minev paid 10 million levs (~5 million euros) for the hotel, and he told the local press that he expects to spend another 10 million renovating it. The plan is to eventually reopen this hotel for business.

Renovation work has started on the hotel already, as can be seen in these images below, sent to me by a colleague. It looks as though they are being careful to preserve the original look and feel of the building. Of course, it will be interesting to see what they do with the interiors also. I do stand by my comments above, that a massive and modern hotel like this does not feel well suited to the kind of tourism that Veliko Turnovo receives – but as a fan of the building, this is one of those times when I would love to be proven wrong. So we’ll have to wait and see. When they get it open again, I’ll be first in line to go and see what they’ve done.

An illustrated guide to urban exploration in the Russian capital.

Poltergeists, ritual murder & a live-in succubus – the 1000-year-old pub with a ghostly reputation

A month-long monument hunt, and what I learned along the way.

COMMENT